In Part I of this two-part article, we talked about the characteristics of two archetypes of client-consultant relationships:

1) Transactional service provider-client relationship

2) Strategic, partnerial relationship

In this part, we focus on helping you determine if you want to pursue a strategic, partnerial relationship in a particular context, and if so, how to go about this.

A: When is a strategic, partnerial relationship worth pursuing?

Building a strategic relationship requires time and effort. Therefore, it may be useful to apply five tests to see if a particular situation warrants building a strategic relationship.

Tests 1-5: Deciding whether a strategic relationship is warranted

Test 1: Does the context warrant the effort of building a strategic, partnerial relationship or will a transactional relationship best serve the situation?

Test 2: Is there sufficient value at stake?

Test 3: Do the key individuals involved have the decision-making power, influence, budget, and personal commitment to shape this relationship creatively, or are they severely limited by other priorities, rigid policies, procedures, and rules?

Test 4: Do the parties have a sufficient set of shared values?

Test 5: Do the key individuals involved bring sufficiently distinct capabilities to the table that there is real potential for synergies? Are they committed to exploring options to realize these synergies?

We will cover each of these five tests in turn.

Test 1: Does the context warrant the effort of building a strategic, partnerial relationship, or will a transactional relationship best serve the situation?

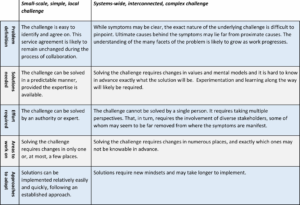

A small-scale, simple, and local challenge is likely to require a transactional collaboration. On the other hand, a system-wide, interconnected, and complex challenge will more often benefit from strategic, partnerial collaboration. The table below illustrates the difference between these two types of challenges.

A structural understanding of the nature of the problem may be aided by referring to the Cynefin framework, as described by Dave Snowden.

The Cynefin framework divides decision-making contexts into five domains, each of which requires a distinct approach: obvious or clear, complicated, complex, chaotic, and disorder. In the Obvious and Complicated domains, best practices and good practices apply. Seasoned practitioners are able to solve the issues based on their experience and insight gathered from earlier cases. In the Complex and Chaotic domains, causes and effects are hard to discern, and causal links may not be discernible based on any available analysis. Finally, in the domain of Disorder, the problem is composite. It may be possible to decompose the problem into components, falling into one of the prior domains.

In the Obvious or Clear domain, qualified labor is sufficient to solve the problem. Transactional collaboration is likely to work well.

In the Complicated domain, deep expertise is required. A deeper trust may be helpful, but causal links can be adequately analyzed by a qualified expert. It may be useful to divide any collaboration into two phases: a diagnostic, where the analysis is performed, and a design, construction, implementation phase where the identified solution is put in place, and the benefits are harvested.

It is in the Complex and the Chaotic domains that strategic, partnerial collaboration comes into its own. In these domains, any attempt at a priori specification of the problem and the solution are misguided – indeed, naïve. The problem must be understood iteratively and solutions must be developed based on incremental experimentation. Multiple perspectives are critical. Asking new questions will help uncover these perspectives. In these situations, deep trust and open communication are de rigueur. Attempts to govern meaningful collaboration based on rigid rules, policies, and contracts are doomed to fail.

For example, it is straightforward for a business leader to find a consultant who can facilitate an annual leadership off-site, run a strategy development workshop, or coach a few individual leaders. In other, more complex contexts, a simple approach based on a simple up-front specification of the work to be done would not work at all. For example, a leading global university based in China chose a strategic approach to working with us to enable their multifaceted 2025 vision. A number of pain points were holding the organization back: a bureaucratic culture that stifled creativity, poorly allocated budget, unclear roles and responsibilities, tensions between central management and faculties, a way of communicating and working together that was often transactional rather than trust-based. A two-month systematic diagnosis resulted in a 1.5-year transformation program in which together we developed the top 100 leaders and strengthened operational practices in financial management, HR, IT, and facilities management. Such a transformation was complex and interconnected, not simple and local.

Test 2: Is there sufficient value at stake?

Building a long-term strategic relationship requires substantial effort from both parties and a high value at stake to justify the investment. For example,

- a global hospitality company wanted to grow its business in China by a factor 10

- a University wanted to streamline operation and free up USD one hundred million per year from administration to enhance academic excellence

We were involved in both of the above cases which justified the investment in a more strategic relationship.

Test 3: Do the key individuals involved have the decision-making power, influence, budget, and personal commitment to shape this relationship creatively, or are they severely limited by other priorities, rigid policies, procedures, and rules?

In the situations where we successfully formed strategic relationships, we have seen that the top leaders of both parties are invested in developing the relationship and shaping the collaboration. For example, the CEO of the global hospitality company and its MD of the China business led the effort, role modelled by participating in regular leadership development workshops, received 1:1 coaching themselves, and led governance meetings to review progress and address issues and risks. Every member of the senior leadership team was deeply engaged in developing their personal leadership, sharpening skills, and shifting mindsets.

We have also seen how such effort failed in the end in some cases, because the senior leaders didn’t invest in the relationship and chose to delegate too early and too much to middle management. For example, while a real estate company in China that we worked with was keen to upgrade its business strategy to meet the challenges of Covid-19 and other changing forces in the market, the CEO and the head of strategy delegated nearly all the work to a manager from the very beginning of the engagement. That led to lack or delay of decision making, and insufficient support from key stakeholders to start initiatives and obtain resources required. In another case, the department head of a global electronics company was keen to develop a strategic partnership with our firm, but he was held back by the rigid and slow procurement process of the company; he also didn’t have the authority required to change the procurement process to enable such a collaboration. It took more than a year for us to contract the engagement, which severely delayed the value creation for the organization.

Test 4: Do the parties have a sufficient set of shared values?

It is critical that the two parties spend time understanding each other’s core values and ensure that they share a sufficient set of personal and organizational values, otherwise, it will be hard to form a long-term strategic partnership. In one case, after working with a collaborator for nearly a decade in various projects, we decided to enter into a long-term partnership. We knew that we shared several critical values such as:

- a) Love: We do our work because we want to use our talents and resources to serve the development of people and advancement of societies.

- b) Generosity: We believe that if both parties are willing to give more, the relationship will end up creating more value for both parties.

- c) Excellence and Professionalism: We are both passionate about delivering excellent work to our clients and to other key stakeholders.

We have also had experiences where the sharing of core values was not present, e.g. we decided to not enter a collaboration where the business leader was focused on doing work for the sake of fulfilling the requirements of the board, while the work itself would lead to wasting the organization resources.

Test 5: Do the key individuals involved bring sufficiently distinct capabilities to the table, providing real potential for synergies? Are they committed to exploring options to realize these synergies?

It is important that the key individuals from the client and consultant side bring distinct capabilities that are complementary and required for realizing their shared vision. Otherwise, the case for strategic collaboration will lack intrinsic motivation. When facing challenges, it may be easy for both sides to walk away from the collaboration instead of committing to resolve the challenges. At the same time, it is also important that both sides are open to hearing the aspirations and needs of the other, and exploring collaboration options that will allow both to bring the best to the table.

In one case, we worked with a CEO who is experienced in coming up with creative business ideas, developing a winning strategy, and building a new business from scratch. However, it was clear to him that he was not passionate about or skillful at building and growing a leadership team. He was also not interested in continuing to enhance the operation of the business so that it had the systems, structure, and practices to scale. He was seeking a partner who could complement him and work with him to build a world-class executive team, and establish the organization structure and practices that would scale – that is exactly where our passion and expertise lie. That created a strong foundation for us to explore options that would help realize the potential synergies. We created a model where we started from working together on a 1-month project with a fixed fee, then moved on to contracting a 6-month program with a monthly run rate. We kept calibrating during the process and became more confident about the collaboration. We then took a bolder move and committed a core team for a 2-year collaboration.

B: Are we going about it in a good way?

If the prior tests lead you to conclude that a strategic relationship is called for, we propose five tests to check that you are forging this relationship in a good way.

Tests 6-10: Optimizing a strategic client-consultant relationship.

Test 6: Are the key individuals involved building a compelling shared vision for the outcome they are seeking?

Test 7: Are the key individuals involved prepared to give one another candid feedback on how they perceive that the collaboration is working, so that they can strengthen it over time?

Test 8: Are the key individuals involved actively investing in the relationship and are they prepared to deepen trust to the level required to achieve the shared vision?

Test 9: Are the key individuals involved in learning and growing through the collaboration?

Test 10: Are the parties both sufficiently Creative and are they monitoring and managing reactive tendencies?

We will cover each of these five tests in turn.

Test 6: Are key individuals involved building a compelling shared vision for the outcome they are seeking?

A strategic, partnerial relationship requires deep trust, which is hard to build during a common journey if we are pulling in different directions. Building a strategic, partnerial relationship requires regular check-ins where we ensure that our respective visions remain aligned – this is not a one-off. As the journey unfolds and we learn more, our vision evolves and becomes dangerous to assume that a shared vision remains shared, unless we spend quality time together validating that we remain in sync.

Test 7: Are the key individuals involved prepared to give one another candid feedback on how they perceive that the collaboration is working, so that they can strengthen it over time?

If there is no turmoil during a transformation journey, chances are high that what the team is engaged in is not very important. Only marginal projects can fly under the radar and avoid scrutiny, challenges, and conflicts. In any complex endeavor there will be regular expectation mismatches.

The proactive way to ensure these do not become destructive is to offer candid feedback in both directions: client to consultant, and consultant to client. What is working well? What do we appreciate about the other party? What do we wish that the other party would start, continue, or stop? What is really damaging? What in the behavior of the other party puzzles us?

Such candid feedback requires and builds maturity. Contracting parties that can maintain a regular cadence of such conversations will see trust deepen, round by round, provided the sessions are conducted with grace, generosity, humility, and candor.

Test 8: Are the key individuals involved actively investing in the relationship and are they prepared to deepen trust to the level required to achieve the shared vision?

Are the individuals involved prepared to bring their whole selves to the collaboration – business and personal life, strengths and challenges? Are they prepared to be open and vulnerable with one another? Do they care about each other’s interests and seek to meet those interests in the collaboration instead of being overly self-centered?

If the sense of interdependence is strong and if the sense of mutual appreciation is high, chances are good that the trust level will continue to deepen and greatly enhance the likelihood of reaching the shared vision.

Test 9: Are the key individuals involved in learning and growing through the collaboration?

A learning mindset makes the collaboration richer. If both parties have the required humility and curiosity, we can achieve an upward spiral where we generate new insight together, shape the way we collaborate for greater flourishing, learn from these changes, and challenge one another productively – leading to new insights and the next round of the upward spiral.

Test 10: Are the parties both sufficiently Creative and are they monitoring and managing Reactive tendencies?

If there is anxiety in the leadership team – on one side or the other – it will be hard to establish and sustain a strategic partnership. Common fears include the fear of not pleasing influential people, not being seen to be in control, and the fear of not being seen to be smart and knowledgeable.

In a complex domain, no leader can please everyone, be fully in control, or have all the answers. Strategic collaboration requires that we detect, name, and confront such anxieties. That way we can manage these anxieties rather than having them manage us. Instead of being pushed by fear, we need to be drawn by a shared, inspiring vision. This is what the shift from Reactive to Creative is all about.

When we operate from a Creative mode, it is easier to adopt an abundance mentality. With this perspective the world is a big, bright place with lots of opportunities. We partner with others to realize more of these opportunities. We are deeply convinced that synergies are real, and that together we can create greater value. The focus is on creating new value, not on allocating existing value. Such a mindset frees up energy to stimulate and inspire one another, so our imagination soars, we visualize new opportunities, and gain the courage to go after them and realize new value.

By applying these ten tests, chances are high that you will configure your collaboration for great success.

Tor Mesoy is the Managing Director of Agnus Consulting, a Hong Kong based firm that delivers strategic consulting services, leadership development, and executive coaching to clients around the world.

Tor has served as a management consultant and leadership development consultant for more 30 years. He was a partner with McKinsey and, before that, a partner with Accenture.

He has led a number of large transformation programs and played key roles in several mergers/acquisitions. He has served clients in all parts of the world including Asia (Hong Kong, Beijing, Shanghai, Singapore, Kobe, Djakarta, Kuala Lumpur, …), America (New York, San Francisco, San Jose, Chicago, Minneapolis, Raleigh, …) and Europe (Paris, London, Edinburgh, Scandinavia). Tor has also led leadership development programs around the world – providing leadership development to more than 4,000 leaders through these programs, and he has lectured on leadership-related topics at several leading academic institutions including University of Oxford, Carnegie Mellon University, and the Norwegian University of Technology and Science.

Yan Liu is a senior executive coach, facilitator and consultant of Agnus Consulting, a Hong Kong based firm that delivers strategic consulting services, leadership development, and executive coaching to clients around the world.

She has over 15 years’ experience in leading teams, managing projects, and designing and delivering organization development programs. Her passion is to facilitate individuals and teams to become more effective at collaborating to solve critical problems and creating sustained, step-wise improvements in performance impact. She has worked with corporations, universities, NGOs and start-ups in mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau, Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, and Europe. She has led or contributed to multiple large transformation programs, primarily in Asia.